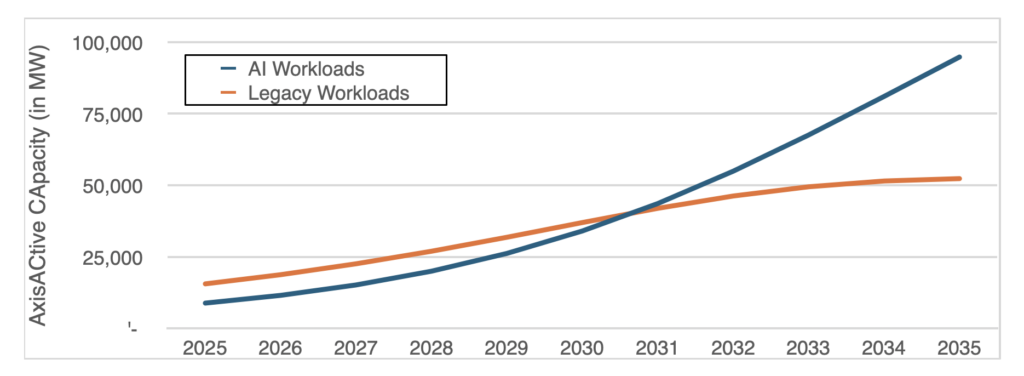

By 2035, global active data center IT capacity is forecast to surge nearly six-fold, from roughly 24 GW today to around 147 GW, as a new ABI Research forecast shows. A staggering expansion driven largely by artificial intelligence (AI) workloads, hyperscalers, and increasing rack-level power density. Compared to previous hypes, this tectonic shift should be front-of-mind for every telco strategist today.

Active capacity by workload-type: world markets, 2025 to 2035 (Source: ABI Research)

One should note that this is growth driven by AI training, inference, and increasingly dense workloads that require far more power, far more cooling, and far more reliable connectivity than traditional applications ever did. Rack densities are rising, power draw per site is climbing, and latency tolerance is shrinking.

For telecom operators, this matters because it changes where value accumulates in the digital stack. Connectivity is still essential – but it is no longer the scarce resource. Compute is, and power is, and the ability to colocate those two efficiently is becoming the real bottleneck.

AI infra exposes telecom’s strategic awkwardness

Telecom has spent the last decade telling investors it wants to move “up the value stack,” while behaving in ways that suggest it’s deeply uncomfortable doing so. The AI-driven data center boom is exposing that contradiction.

AI workloads are latency-sensitive. They increasingly need regional or metro-level compute. They benefit from tight integration between network, edge facilities, and cloud platforms. On paper, this should play directly into telco strengths: distributed assets, local presence, spectrum, fiber, and enterprise relationships. But in practice they are stuck somewhere in the middle.

They are too infrastructure-heavy to pivot quickly like cloud-native players, and too culturally risk-averse to compete directly with hyperscalers. So they default to partnerships that are safe, incremental, and – crucially – value-limiting.

What’s interesting is that the next wave of cloud growth may not come exclusively from the usual hyperscaler trio. Smaller, AI-focused cloud providers are emerging that care deeply about where compute lives and how it connects to users. These players don’t necessarily want to own fiber, towers, or metro networks — but they do need them to work exceptionally well.

That creates an opening for telcos. Not to become cloud providers themselves, but to become unavoidable infrastructure partners. The problem is that many operators still sell connectivity as if it were the product, rather than as part of a broader infrastructure capability tied to compute, locality, and performance guarantees.

Why power and grid access are the real bottlenecks

There’s a simple reality behind the data center growth story. Data centers don’t scale because demand exists. They scale when power and grid capacity exist.

AI workloads are now running into electricity constraints, particularly in Europe but increasingly elsewhere. Projects are being delayed or downsized not because customers aren’t ready, but because the grid cannot deliver enough power where it’s needed. This goes beyond generation. Transmission limits, substation capacity, and slow upgrade cycles are becoming real blockers. Cooling only makes the problem worse.

The issue isn’t power in the abstract. It’s grid access. That makes this a physical, regional problem shaped by permitting, municipal coordination, and long planning timelines. In other words, this is an infrastructure problem, not a cloud problem.

Telecom operators should, in theory, have an advantage. They already manage physical infrastructure, work with utilities and municipalities, and operate metro and edge sites close to constrained parts of the grid. Historically, those assets were optimized for coverage and cost. Going forward, they may need to be optimized for strategic optionality, where power, grid access, and compute placement converge.

The alternative is familiar. Becoming a highly efficient delivery mechanism for someone else’s AI infrastructure, connected to data centers operators had no role in shaping and no leverage over once they are built. As the industry has learned more than once, that role rarely comes with premium margins.

Leo Gergs is principal analyst at ABI Research, leading the firm’s enterprise connectivity and cloud and data center research. His work covers enterprise drivers, use cases, and provider strategies for technologies such as private cellular, SD WAN, and Fixed Wireless Access. He also analyzes key trends shaping the data center market, including the rise of neocloud providers, the growing importance of sovereign cloud models, and their implications for enterprise infrastructure, regulation, and workload placement.