A panel at PTC in Hawaii comprising hyperscalers Google and Meta and wholesalers Exa Infrastructure and Southern Cross Cable Networks explored how AI is reshaping demand for submarine cables, driving hyperscaler-led builds, stressing legacy systems, and creating new regulatory and supply-chain challenges for the industry.

In sum – what to know:

Exploding demand – AI is reshaping subsea cable infrastructure, with new trans-atlantic/pacific routes needed; but aging systems, challenging business cases, and regulatory and logistical constraints abound.

Changing models – wholesalers like SCCN and Exa have shifted from serving carriers to hyperscalers; operators face challenges with rising bandwidth, capacity allocation, and strategic network planning.

Mounting problems – deployments are constrained by tech roadmaps and supply bottlenecks; plus there are major disconnects with data centre builds, terrestrial fibre projects, and government intervention.

More notes about the state of the subsea cable industry in the AI era – taken from a panel session at PTC in Hawaii a couple of weeks back, some of which has been covered in these pages already. Note, this will be a shorter round-up than last time, given time constraints at RCR. The discussion so far has been about transatlantic subsea infrastructure, and the need for new cables between North America and Europe. As we were; Jim Fagan, chief executive at EXA Infrastructure, says his firm is looking to build new cables in the region, possibly to the north.

“The north… has kind of been neglected, and [you] think where [new] data centers are going… [into] the Nordics,” he said. “There’s demand… [and] we think it might be time for another one, and we look to go forward with that. It’s absolutely going to be a Northern Atlantic route.” Just for context, cables will go to wherever there is power, and a business case for a data centre – rather than the other way around. “Theoretically, we can build subsea cables anywhere,” said Nigel Bayliff, senior director for global submarine networks at Google.

“There is a move to [build data centres in] Scandinavian countries, where there’s more power and it’s colder. Taking cables to the high Arctic… is probably more feasible than moving a data centre to a hot country with an easy place to land a cable. If you think of the amount of money being spent on data centers versus the amount on subsea cables, then it’s entirely appropriate that we just go to where they are.” Interestingly, Bayliff also made the point that subsea infrastructure is simpler to set down, often, than terrestrial fibre networks – even given the bureaucracy involved.

“It is the terrestrial networks that are hard to get to the levels needed for some of these large deployments – quickly. It often takes longer to sort out four or five routes through remote parts of Finland than to land a cable on the Norwegian coastline.” It’s not just in the Atlantic, of course; the subsea crunch is global, variously, as demand spikes on new AI ventures and legacy systems, built for the last big tech bubble, become obsolete. Laurie Miller, president at Southern Cross Cable Network (SCCN), owns trans-pacific cables that were commissioned in 2000.

He reflected: “Our system went in 25/26 years ago, so it’s end-of-life. We’ve enjoyed a good run there – 21 years as a dominant provider on that route. There’s obviously demand; Australia is becoming more critical from a geopolitical point of view – in terms of data centers and connectivity on a southern route. Demand is pushing the need for better supply under water. But we’re a wholesale operator like Jim and the struggle is the business case. That is the hardest justification.” The last part, here, is worth unpacking – in case you don’t know.

Hyperscale systems

Miller’s point is that wholesalers like SCCN and Exa used to serve terrestrial telecoms carriers, needing international capacity for voice and early internet traffic. The old model was that it served a relatively small number of telco buyers on predictable long-term contracts. SCCN is owned by carriers – as a joint venture by Spark in New Zealand, Singtel-owned Optus in Australia, Telstra in Australia, and Verizon Business in the US – and so its incentives were aligned: carriers needed trans-national capacity, and it owned subsea cable to cross the Pacific.

But new demand is not from traditional carriers, any longer – it has been coming from cloud companies for a decade, at least, and is newly exploding with their AI agendas, especially in Australia and along new “southern routes”. Miller noted: “The carriers are not the hyperscalers; they’re selling to the hyperscalers. The demand drivers have changed, and we have to change with that.” The point is that, even despite rising demand in a crucial region for traffic growth, carriers are no longer the end customers, and hyperscalers have routes of their own and crazy buying power.

He added: “The hyperscalers are our customers. That’s the bottom line. We do not have organic growth… AT&T used to be the dominant [player]; it was the carrier club. We were part of it. But we will evolve… We know who our customers are, and… we [know] there’s opportunity and we know there’s a risk also – because we have to find the right partner, and work with them to understand where to build. We’ve got to do the dance with the financiers and shareholders, and bring that together. It is no simple task, but history says we’re up for it – that it’s what we do.”

His comments reveal the challenges in the broader industry, as well as the tensions on the panel – between the old subsea mariners and the new lords of the deep. There is a challenge as well just for subsea wholesalers to get a couple of open channels on the latest fibre crossings, as set down by the likes of Google and Meta. Fagan at Exa remarked: “It is wonderful they have all this demand, and they’ve got the cash to build… [But] traditionally, a quarter to a third of [their capacity] came back on the market…. [and now] they’re getting told to keep it all.”

He went on: “I get the question [about whether AI will] derail us [but] the fact is we see… how AI is used. Back in the day, financial services wanted one gig or 10 gig; they’re all now asking for 100G or 400G because they’re ingesting their data into their AI models… You can see where this growth starts to explode. The issue is that they’re beholden to their use cases, and those are starting to get stretched. So this is the time where, as a wholesale industry, we have to come together and figure out how… to build into that global traffic mesh. It’s going to be a big mindset shift.”

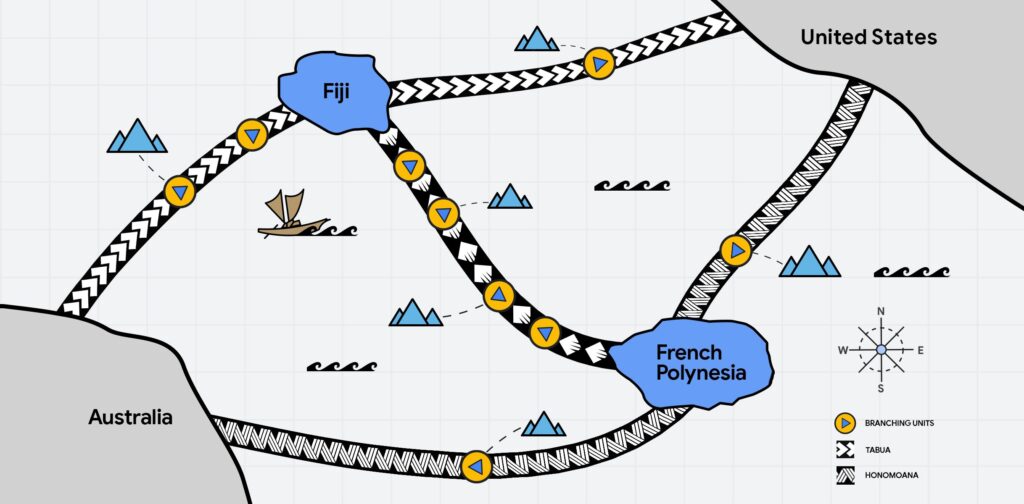

Bayliff reassured that Google’s two new trans-pacific cables (Honomoana and Tabua, part of its South Pacific Connect project; “about to complete”) will return capacity to the open market. “Six of the fibre pairs on each of those went to commercial parties. The plan is probably eight and eight, and one of the cables will have a different allocation mix.” In other words, each system will have eight fibre pairs, in line with modern subsea designs, and that one of the two cables in each will serve more routes or different branching paths – cater to different commercial requirements.

Commercial access will vary slightly depending on route complexity and strategic use, but wholesale carriers, telecoms providers, and big multinational enterprises will have access to capacity, either by acquiring full fibre pairs or spectrum on the fibres. He added: “The overall intent is that, under our standard model, carriers and participating parties will always be able to access those systems at the fibre-pair or spectrum level.” What does Meta say? The question was posed by the panel host, Thomas Soerensen, in charge of subsea solutions at Ciena.

Will Meta use all the capacity on its new routes? Nico Roehrich, director of network investments in the APAC region at Meta, responded: “It is difficult to say. We have six fibre pairs in production, [and] we never imagined we would need all six. We also didn’t imagine it would take twice as long as the original plan. So it’s a little bit [like] insurance. We want to go as big as we can so we have the flexibility. We are a critical part of the ecosystem, and we’ve invested in consortia systems for years… We’re aware of our role and want to be respectful. But the lead times…”

Disconnects everywhere

Indeed, Roehrich is hitting on the broader challenges to deploy subsea cable. Bailiff’s earlier point that it is simpler to deploy than terrestrial power or fibre to data centres might be right, but it’s still a complex undertaking – and becoming more so. The business case is complex, the panel agreed, and the technology no longer affords much flex for future capabilities. “We’re way closer to Shannon than ever before,” said Roehrich, citing Shannon’s law, defining the theoretical-max for error-free data over a comms channel with a specific bandwidth and signal-to-noise ratio.

It is the standard explanation as mad-paced tech innovation tests the laws of physics. He explained: “We’re not going to have the same level of upgradability as in the past. Meta is focused on building the fattest cables it can – because we don’t see the same gains as in the past. Which speaks to the business case, of course. Because you know the total capacity of the cable from day one pretty much, and you can’t factor in the kind of future incremental gain that you used to be able to.” As above, the case is also complicated by long lead times for new fibre optic cables.

It is a natural consequence of a hyperactive market, of course, plus supply-chain bottlenecks (too few manufacturers, vessels, vendors) – exposed during Covid and exacerbated by demand. “We’ve gone from 18 months to 48 months as the standard lead time to build a cable,” said Roehrich. “The combination of long lead times and less upgradability is a challenge.” But there are “disconnects” everywhere, it seems – with data centre builds, with terrestrial fibre deployments, and with governments around funding and regulation. The panel picked through these issues in turn.

Miller at SCCN said: “We’re in a cycle. It is disjointed at the moment. I don’t think there is a lot of coordination between data centres and submarine cable systems, and the investment cycles are so different. We’re building a 25 year asset and an [AI] chip is obsolete in two years. So trying to marry those two investment cycles is really hard.” Fagan at Exa had a similar story, suggesting there remains a misperception, in some quarters, that operators can “drop in 96 or 144, or even bigger” onto a standard 24 fibre-pair subsea system – as they would on land.

The difference is a subsea system, once deployed, is fixed, and also hugely capital-intensive and constrained by ship times, manufacturing slots, and route permissions. “They think subsea and terrestrial are the same,” he said. You can’t overbuild, parallel-build, or re-pull fibre under the ocean – like land lubbers among the fibre community. He added: “There’s this disconnect with the investment cycle and the cost and the timing of it. Wherever you’re going, there will be wash-outs where some facilities are over-financed and don’t get connectivity.”

Roehrich chimed in: “We’ve definitely seen announcements withdrawn – where people say they are going to put a data centre here because they’ve got megawatts of power, and then [cancel the project] three months later because they can’t connect to it.” The point is to do due diligence on new projects, responded Fagan. “We look at the feasibility of the facility before building to it – because I have finite capital. A lot of the data-centre money over the last three years [unravels] as facilities become operational and don’t have the right connectivity.”

But on balance, most of the panel’s ire – or discussion, anyway – is about government funding and regulation. Part of the issue, and opportunity, is to work with governments on the reuse of cable routes and landing stations – with a view to “cut off a year or two” for new deployments. “It [would make] a big difference right now if you look at the capacity [demand],” said Fagan. Meta would like to reuse some infrastructure as cables retire, said Roehrich. But there are issues, sometimes – newly-formed/designated marine sanctuaries over the top, he suggested.

“There’s a real opportunity for industry and government to work together to figure out how to make this easier.” Roehrich, in particular, was candid on the panel about government collaboration. “For most of what we need, we couldn’t wait for government decision making timelines,” he said. “There must be others, maybe with less capital than us, who can… [wait for] government funding to build something unique, but, for us, time is the most critical.” But Meta’s biggest headache, it seems, is getting government approvals to plan, lay, and operate submarine cables.

Government oversight

These include national permits from coastal states to enter territorial waters, environmental approvals to navigate fisheries and marine ecosystems, right-of-way permits with port authorities and local communities, and various other coordination to cross geographic territories and economic zones. Plus, there are danger zones, of course, where subsea cables get, intentionally or unintentionally, dragged by anchors from fishing boats. For Meta, this is the daily grind, and sufficient for its massive Project Waterworth to take weird routes to navigate regulatory bottlenecks.

Project Waterworth represents the world’s longest undersea fibre‑optic cable system, spanning about 50,000 kilometres and linking five continents. Roehrich explained: “It is very much driven by diversity. More diversity is better, in terms of where the cable lands and where it’s routed. Not surprisingly, permitting is a major driver. It is a case of where we think we can build, with the most predictable permitting, or the least likely to go sideways… It is one of those things where we’re uniquely positioned to build something that really doesn’t make a lot of sense.

“If you look at the routing, there are some deep water benefits, but it is more expensive than going from A to B on a traditional route. If we were to try and sell it, I assume there would be no interest because the latency is so high. So for us, it was really [about] insurance. The question is whether that insurance policy ever pays off. But overall, we are being driven by governments and policy decisions to go to new places – which is net beneficial for resiliency in the network, for the ecosystem as a whole, but probably doesn’t make sense for traditional telcos to invest.”

The other government tangle for the subsea sector, as discussed at PTC, is with the industry’s new designation as “critical infrastructure”, reflecting the recognition that submarine cables are important (more than) to national security, economic stability, and digital sovereignty – and in process variously in Europe, NATO allies, and UN forums since 2023/24, precipitated also by rising geopolitical tensions. But some kind of disputed additional responsibility comes with the designation, as the EU, notably, seeks to introduce naval vessels to patrol infrastructure in the North Sea.

Fagan responded: “It’s a really big topic; we have these discussions with the EU, UK, US, and, not to be selfish, but we get asked [to provide] security… And for a private operator, it’s like, yeah, if you want to help me pay for it… Right now it seems to be a bit more than talk; like there is some action. Governments are trying to get their heads around it… It’s like a new paradigm – like soft warfare or soft power. The good news is the conversations are there, and the education has happened. But as far as tangible solutions go, which let me sleep better at night, [there’s work to do].”

About PTC: The Pacific Telecommunications Council (PTC) conference is a four-day event held annually in January in Honolulu, Hawaii. It serves as a major hub for global digital infrastructure, telecommunications, and ICT (Information and Communication Technology) industry leaders to collaborate, connect, and discuss industry trends like AI, subsea cables, and satellite networks.