No one has yet defined what 6G actually is, let alone how it will succeed economically

Editor’s note: This is the first installment of a three-part series from Analyst Vish Nandlall. Keep an eye out for parts two and three, coming soon.

Every mobile generation has been more than just a technical upgrade. It has been an economic story about how value is created, delivered, and captured. 3G, 4G, and 5G each came to market with a well-formed business model and a clear basis of competition. They grew in the context of expanding device penetration and unmet demand, giving operators room to capture new value. But as the industry now peers toward 6G, one fact is glaring: No one has yet defined what 6G actually is, let alone how it will succeed economically. The table is not set for success.

| Feature | 3G (The Catalyst) | 4G (The Revolution) | 5G (The Bifurcation) | 6G (The Dilemma) |

| Era | Mobile Telephony | Mobile Compute | Mobile and Edge Compute | ? |

| Primary Value Created | The possibility of the mobile internet. | The mobile-first app economy. | Competitive broadband alternative (FWA) & urban capacity relief. | Unclear. A “network of cognition” for speculative use cases. |

| Basis of Competition | Coverage & Basic Reliability. | Speed & Network Performance. | Mid-Band Spectrum Depth. | Unclear. Extreme performance metrics with diminishing marginal value. |

| Key Demand Driver | Initial adoption of mobile/wireless devices. | Explosion of smartphone penetration and app usage. | Demand for home broadband competition; urban data congestion. | None demonstrated. Assumes future demand for AR/VR and sensing. |

| MNO Revenue Growth (CAGR, Peak Rollout) | N/A (Pre-IPO/Early Data) | ~4.3% (Verizon, 2010-2015) | ~0.6% (Verizon, 2019-2024) | Speculative. |

| MNO ROIC vs. WACC | N/A | > WACC (Value Accretive) | ~ WACC (Value Neutral/Destructive for some) | << WACC (Highly Value Destructive under current cost projections) |

3G: The mobile internet

3G emerged in the aftermath of the dot-com and telecoms crash, when capital was scarce and skepticism was high. Its value proposition was simple but powerful: mobile access to the internet. Email and basic web browsing went from tethered desktops to handsets. Operators monetized this shift through tiered data plans, and the basis of competition was coverage and reliability. It was not glamorous, but it created a durable new revenue stream that carried the industry through a period of financial retrenchment.

Macroeconomic context mattered. Global mobile penetration was still in its growth phase, with vast populations yet to be connected. Investors, though cautious, saw upside in subscriber growth. Average revenue per user (ARPU) was modest but growing steadily as consumers shifted from voice and SMS to data bundles. Capital intensity was high, but the incremental revenue justified the spend.

4G: Mobile apps and video

If 3G made mobile internet possible, 4G made it indispensable. Launched in a market already primed by the iPhone and the App Store, 4G was the perfect enabler of the mobile-first digital economy. Video streaming, social networking, and ride-sharing became mass-market realities. For operators, this was the golden age: consumers willingly paid for more data, unlimited plans proliferated, and network speed became the new competitive benchmark. The value was clear, the customer need was proven, and operators captured meaningful growth.

The macro context was equally favorable. Smartphone penetration skyrocketed from under 20% in 2007 to more than 60% by the mid-2010s. Data consumption per user grew at double-digit annual rates. ARPU held firm, even rising in many markets as consumers upgraded to larger data packages. Capital expenditures were significant (eg spectrum auctions and LTE rollouts consumed billions) but operators enjoyed revenue growth that exceeded cost of capital. In the U.S., Verizon’s revenues rose from $106.6 billion in 2010 to $131.6 billion by 2015, a compound annual growth rate of 4.3%. Investors rewarded the sector, and for once, telcos captured a meaningful share of ecosystem value.

5G: eMBB, edge, and FWA

5G promised to repeat the 4G playbook: faster speeds and revolutionary new use cases. Enhanced Mobile Broadband (eMBB) was meant to lift consumer experiences, while edge computing and ultra-reliable low-latency communications were touted as enablers for the enterprise. In practice, however, 5G became a story of incremental gains. For consumers, the difference was faster downloads, this proved useful, but not transformative. The enterprise revolution never materialized at scale. Instead, Fixed Wireless Access (FWA) emerged as the lone breakout, finally giving telcos a credible way to challenge cable broadband. Otherwise, 5G has largely been a churn-management tool, a way to keep customers from defecting rather than a new growth engine.

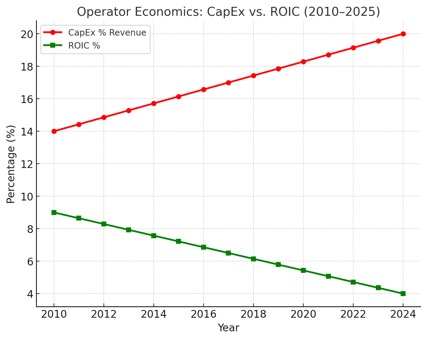

Here the macro context was far less forgiving. By the time 5G launched, mobile penetration in advanced markets had reached saturation (over 100% SIM penetration in many countries). ARPU had been in steady decline for years as competition intensified and regulators pushed down roaming and termination rates. Capital intensity soared, with global operators spending more than $600 billion on 5G networks by 2023. Yet revenue growth barely budged. Verizon’s CAGR from 2019 to 2024 was only 0.6%. Returns on invested capital struggled to exceed weighted average cost of capital, raising serious doubts about whether the generation created or destroyed shareholder value.

The question of 6G: What is it?

This brings us to 6G. Every past generation had a clear answer: 3G was the mobile internet, 4G was mobile apps and video, 5G was eMBB and FWA. But what is 6G? No consensus exists. Futuristic visions like the “Internet of Senses” or holographic communications capture imagination but crumble under economic scrutiny. Without a clear value proposition, 6G risks becoming the first generation launched without a defined business model.

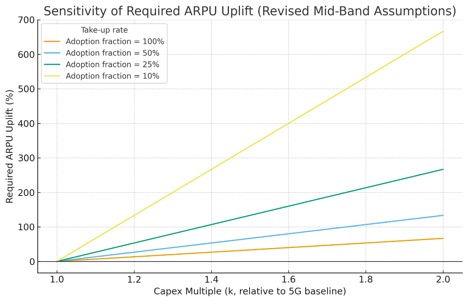

The economics are daunting. Mid-band 6G, the most realistic path, demands 20–100% higher capex than 5G. That could work if adoption is broad, requiring only a 10–30% uplift in ARPU. But if 6G is niche (say, only 10–25% of consumers use premium AR/VR) ARPU would need to rise by 100–275%, levels the market has never tolerated. In short, the numbers don’t add up.

Meanwhile, the macro context is even harsher than for 5G. Penetration is already saturated, leaving little room for subscriber-driven growth. ARPU continues to face downward pressure from competitive bundling, OTT substitution, and regulatory intervention. Capital markets are increasingly skeptical of telcos’ ability to generate returns, punishing operators whose ROIC lags cost of capital. With capital intensity projected to climb again, operators face the prospect of higher spending with no clear path to monetization.

The strategic crossroads

The industry cannot assume that performance improvements alone will generate demand. Once a network is “good enough” for 4K video and mobile apps, incremental gains in speed or latency no longer move markets. Without a new basis of competition, operators are left holding the bill for infrastructure while hyperscalers and device makers capture the application-layer value.

This is the value-capture crisis at the heart of 6G. The technology roadmap is rich with possibilities, but the business logic remains absent. Unless the industry defines what 6G is (not technically, but economically) it will risk becoming a $600 billion exercise in building the world’s fastest bit pipe.

The stakes

The progression from 3G to 5G teaches us that technology alone does not guarantee success. 3G, 4G, and 5G each are aligned with a clear economic context, expanding penetration, and an identifiable basis of competition. 6G, by contrast, stands at a crossroads without a defined model. The table is not set. Unless operators and standards bodies anchor 6G to proven demand drivers and sustainable business models, it may go down in history not as a revolution, but as a cautionary tale.