SailGP’s F50 catamarans are like the biggest and flashest IoT devices on the planet; they capture video and telemetry data which is transmitted on a portable private 5G system from Ericsson at a dozen race stops around the world, and delivered every time to a central cloud operated by Oracle in London – where it is processed and returned in real time, to race teams, operations teams, broadcast teams, and fans. The firm’s CTO explains…

In sum – what to know:

Top-level sailing tech – SailGP’s F50s feature a bounty of IoT sensors and cameras, producing 360,000 data points per second for race-day analysis

Cloud and 5G backbone – Oracle’s cloud handles all video and telemetry data in London; Ericsson’s private 5G provides live boat-to-shore comms.

Sustainable broadcasting – Remote broadcast production reduces on-site staff, travel, and costs, and sets a new standard for live sports coverage.

Seafaring tech is everywhere at Portsmouth dockyard, of course: from the high-castled design flaws in the 16th century Tudor carrack Mary Rose, to the 32-pound guns and mixed-timber hull of the 18th century warship HMS Victory, to the iron-cladding of the 19th century steam-powered frigate HMS Warrior. From a distance, you might even get a look at a big naval destroyer, heading home or heading off. A couple of weeks back (actually, a month ago now), RCR Wireless joined a media tour of cutting-edge seafaring tech of the non-military racing kind: a dozen F50 catamarans, being fitted together and hoisted into the Solent for the UK leg of the international SailGP competition. These must be the biggest and most expensive IoT devices in the world, said someone on the dockside.

Was that you – who said that? The question is for Warren Jones, chief technology officer at SailGP, who provided some of the commentary (and most of the conversation) on the day, catching up on a call after the race has finished. “Yeah, that was someone else,” he responds. “But they are [big and expensive 5G-based IoT devices].” He laughs; it is a fair observation, then (by someone else). “They are IoT devices; they send 53 billion data requests [each race day]. We manage video, telemetry data, and voice from them, and we need to get all that information to shore to disseminate everywhere, wherever it is needed.” How it does that is as interesting, in its way, as anything the grand Mary Rose exhibit or the old sea dogs on HMS Victory have to say – if you’re a trade hack in the telco game, anyway.

This is the best press tour RCR has been on for a while.

The thing about the SailGP competition (actually, the Rolex SailGP Championship), between a dozen international teams racing F50s at up to 100 kilometres per hour in open waters, is that it uses technology as a leveller, as much as an accelerant. It is presented as a rival to the America’s Cup, and as a counterpoint on the grounds all race teams use the same ‘one-design’ boats and share the same race data – to prevent “secret arms races”. Part of Jones’ tech remit is to support ‘fairness and transparency’, as per the SailGP press materials. More sensors, better insights, faster delivery – depending on how they are used, these things give the race teams an edge. But they inform their stewardship of the craft – to navigate the course, conditions, competitors – and not how different boats are made.

Because the boats are all the same; any iterative digital-twin design breakthroughs are shared by this ‘one-design’ principle. On the harbour, the ‘wing’ (sail) is joined to the twin-hulled platform ahead of the race; to be disassembled, shipped, and reassembled at the next port of call – Sassnitz in Germany (at the time) on August 16-17, and then St Tropez in France on September 12-13.

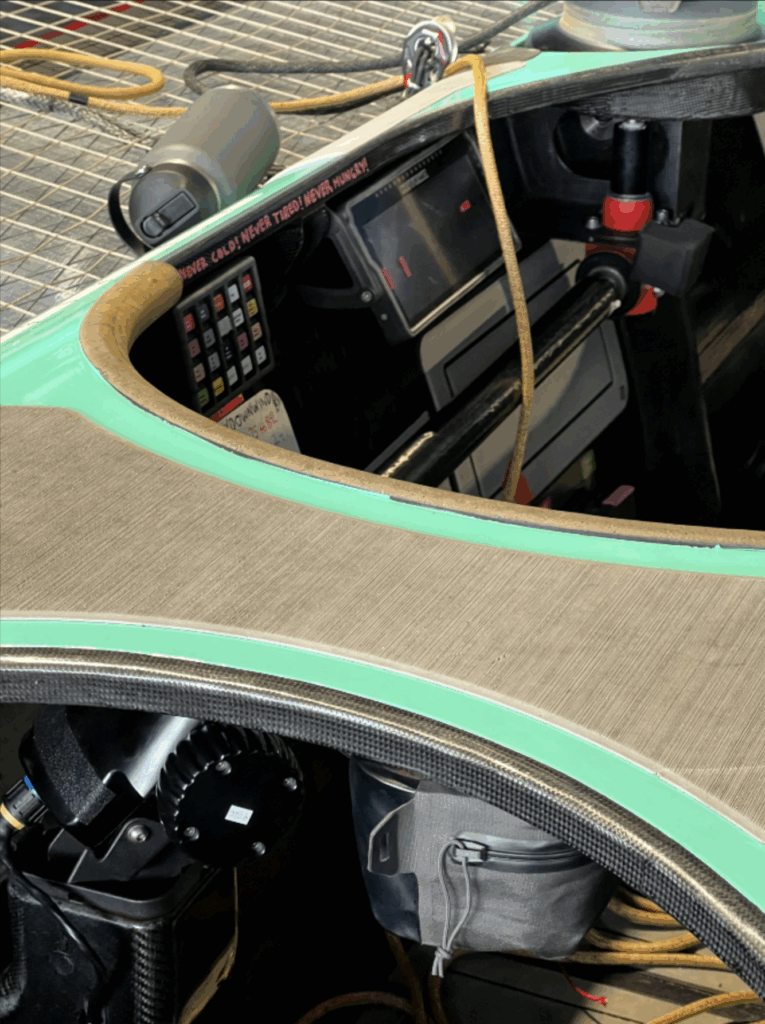

Jones says: “That’s what you saw in Portsmouth, being launched into the water.” Both the wing and the platform are fully “sensored-up”, he says. “We can tell how many times the crew has pressed a button, what fraction they’ve turned the wheel, the camber of the wing, the rudder differential, the forces on the foils… We plug that into our system, and send it back to shore, and back to the cloud in London.”

Central cloud

Time to introduce its tech partners, perhaps. Oracle is in charge of the cloud and edge functions, and has been since the first SailGP boats were launched in 2019. Really, its compute infrastructure makes the whole thing tick; ultimately everything – “360,000 data points per second,” when the race is live – goes via its data centre in south London, where it is flushed through Microsoft’s Azure Stream Analytics.

This is the case wherever the grand-prix event takes place – whether in Portsmouth or Germany, or New York or Sydney. “We’re sending zeros and ones; it doesn’t make any difference what the data is – it could be the GPS location of the Australian boat versus all the other boats. All this data is available to us, and we use the metrics or configurations within Stream Analytics,” says Jones.

SailGP calls them “patterns”, he says, which it “configures… to work out what we want to do”. He says: “We have 10 stakeholders: broadcast, digital and social, the individual teams, the team HQ, where we monitor the boats – how they’re performing, any maintenance, whether they are safe to race. All the different stakeholders get the information they need to do their job.”

As well as simple sensors on the F50s, there are cameras everywhere: 53 in total, in the boats themselves (five on each), plus on two helicopters, four chase boats, three broadcast spots on the harbour. “We need to get the video back to shore, to send to SailGP Productions in Ealing.” Ealing, by the way, is in west London – so there’s another loop, too; from global shores on race days, via the Oracle hub in south London.

The only variation in the architecture is in the southern hemisphere, where regional ‘edge’ data centres are engaged to reduce latency for the live race comms with the boats. Jones explains: “When we go to Auckland or Sydney – or like we went to Perth this year – everything [still goes] back to London… but we use edge servers in Oracle’s local data centres… if we need to get the data back to the F50s. We have dedicated fibers available to us for a round-trip from Sydney, say, to London, and it’s about 150 milliseconds [each way] – so 300 milliseconds [in total], which is still viable. But we need to get that (whether the one-way or return is not clear) under 100 milliseconds – so we use the edge components to work out what to send back to the F50s, and everything else goes back to London.”

Edge network

As per recent headlines in RCR, new tech partners have joined the fray to make part of this short-hop data exchange slicker, between the boats and the shore. Ericsson is SailGP’s new ‘global technology supplier’, and host of the Portsmouth tour; it is supplying a carry-on private 5G network for Jones’ whole elite-level travelling-circus tech endeavour, wherever it pitches up. In the new setup, those 360,000 per-second data points, mentioned earlier, all go via a pair of Cradelpoint routers on each of the F50s to its private network on the shore – and then forward on fibre to Oracle’s servers and studios in London (and back).

Jones says: “Ericsson is a great partner. It has really helped us find the nuances. It has got different industries where it has tried this, but it has never put it on a sailing vessel that goes 100 kilometres per hour on the water. So it is learning, just as we are.”

The Swedish firm actually joined part-way through season four (SailGP skipped the Covid-19 season) last year to test the setup; it has been an ever-present ever-since. “We had a load of Ericsson engineers on site, and they had carte blanche to do whatever they wanted – because it wasn’t operational… We got to a position where we said, ‘this is really a thing; something we could do’ – [in terms of] the setup time, the amount of equipment, the amount of people,” he says.

“We are in our European season now, and we’ve got back-to-back events. By the time we finish on a Sunday, the boats and equipment need to be packed very quickly for the next event. We are looking to improve, get better, be more efficient; and 5G ticks all the boxes. Ericsson pushed really [hard] last season, and we’ve been pushing [harder] this season to see where the line is with this technology. We are in a good position where we know the [setup and] limitations. Going into season six, we’ll push even harder.”

On the dock in Portsmouth, with some prompting, Jones calls the private 5G setup a “revelation”; on the phone later, he describes it a “major milestone”. SailGP was using microwave technology in the 3 GHz band for its race comms previously, which is the default delivery service for wireless cameras feeds. “It is what they use on the pitch side when you watch a football game,” says Jones.

“It is pretty robust and it has been around for a long time. But it requires a lot of people to help do it. And SailGP doesn’t like to rest on its laurels. We want to push the narrative – and we think 5G is a more simplistic technology for what we need to do.”

And the challenge with private 5G spectrum, to get local licences from regulators or local concessions from operators, is much the same. “You need to contact the local authorities, just the same,” he says. “We’ve got great [5G] partners in different countries, and we only need the spectrum for four days at a time; it’s not like we need it for two weeks or a month. So we work with them in the locations we go to, and they’ve been really helpful.”

Transit slice

Related, there is a complementary 5G piece, as well. BT sliced its (southern Nokia-made) public 5G network for the Portsmouth event, just as T-Mobile sliced its public 5G network for the New York leg. There was some confusion in some quarters – like BT was delivering the comms for the whole UK race. But actually, as important as slicing technology is to the event (and Jones is effusive), it is an auxiliary component, deployed because of a quirk of the race environment in Portsmouth and New York (and other stops, presumably) – or because of the limited reach of the private 5G setup, if you prefer.

Jones explains: “It is difficult to find a location for a pit row for 12 international teams, close to the [race] water. We couldn’t do that in Portsmouth [and so the boats were kept] in Southampton, a 40 minute transit to Portsmouth. We can’t cover the whole of the Solent with private 5G; it’s just impossible. We don’t have the time or the funds for that. So BT configured a private slice on [a dozen] existing cell towers to connect to the boats between Southampton and Portsmouth. One of the safety aspects is to have 100 percent comms to the boats – for the telemetry, to know they’re safe to sail, all those things. So to have that on the way to Portsmouth was pretty amazing. It really was. And then, once they are in the race box in Portsmouth, which we control, the private 5G network takes over.”

It was the same with T-Mobile in New York, he says, to connect the boats between the pit row in New Jersey and the race box in Brooklyn, in New York. “The next sites we go to are all single sites,” he says. The pit row is right next to the race box. [But slicing technology] helps when we get these [geographic] anomalies.”

Total impact

But, in the end, the real transformation is from the Oracle cloud architecture, particularly, and the Ericsson private 5G setup, just recently. “No question,” he responds, when asked about the logistical impact of carting about fewer servers and fewer radios.

“Ericsson has helped with the 5G element, and Oracle has helped with the cloud instances. We don’t have any servers on site. Everything is in the cloud. We don’t have so many people on site because they work remotely. Our director, producer, video operator – everybody is in London. We take the video and create the show, which is distributed to 158 broadcasters around the world.”

He adds: “The sustainability angle is important. There are 120 people in our TV studio (SailGP Productions in London, referenced earlier) – which is 240 flights we don’t have to make for each event. It’s also about consistency. We’ve got the same people in the same seats doing the same thing – rather than different people doing it in a different truck in a different country with a different system. We’re human, and the more [we do] things, the better we are at them.”

Its remote cloud production model in London, helped by tactical private 5G transmissions at the race site, puts SailGP on poll among sports broadcasters, he reckons. “The industry wasn’t there when we started in 2019. And a lot of experts told us it was not the way; that we should be doing live [on-site] broadcasting. But today, it is what everybody does; this is how it works. So we were ahead of the game then – with no [edge-based] servers and no [edge-based] data; by investing in infrastructure, including private 5G, to [get data to] where we need it to go. That was not the industry standard. Now it is; all the sporting roadshows on TV are doing the same thing. So we’ve disrupted the industry and hopefully people are taking notice.”