SGP.32 promises to untangle IoT’s complex eSIM provisioning challenges — but its implementation remains a tough nut for the industry to crack (and just to explain).

In sum – what to know:

Urgent needs – roaming restrictions and data sovereignty laws have fragmented global connectivity.

Legacy tech – old eSIM standards struggle with operator control and user-driven activation limits.

New solution – the SGP.32 standard promises a flexible approach for large-scale IoT; but it’s hard.

The introduction of the new SGP.32 standard for remote provisioning of embedded SIMs (eSIMs) in IoT devices is supposed to make IoT fleet management easier. So why is it such a head-wreck? How does something built to hide complexity apparently create more of it? And does that mean that the IoT industry has failed – itself, and all of its customers? Well, no; but it is going to take a lot of work for the ecosystem to order and explain, and make it simple.

Let’s back up… We know why the GSMA, with help from the whole industry, has put in place the new SGP.32 mechanism for provisioning airtime in eSIM-based IoT hardware – because a mix of regulatory, technological, and commercial pressures have variously combined to make its forebear standards obsolete, and forced the IoT market to change. Firstly, there are limits, entrenched and escalating, on how IoT devices roam onto cellular networks.

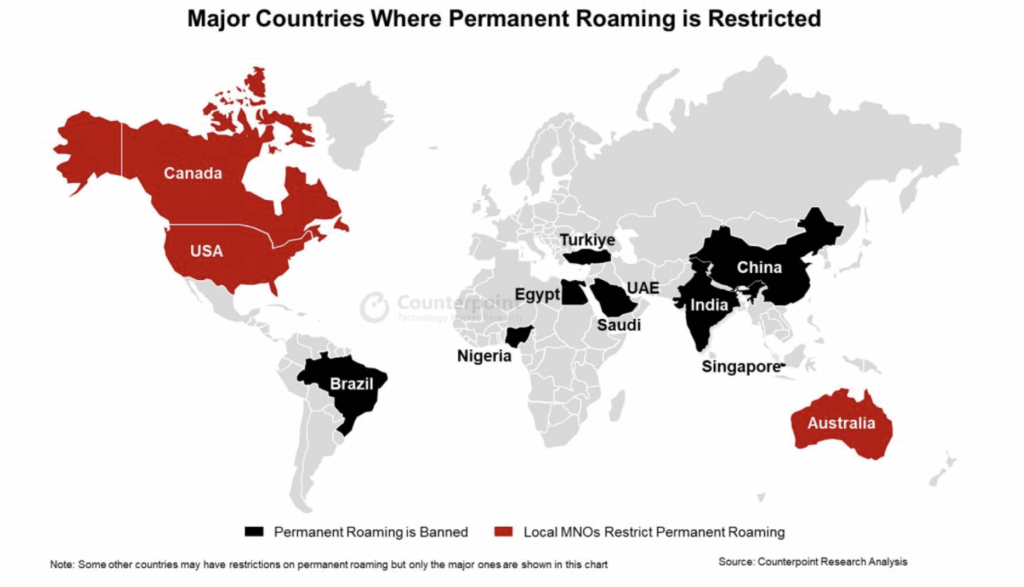

This is not standard practice; it is just another example of the fragmentation in telecoms, and in (cellular and non-cellular) IoT in particular – which is a symptom variously of government control, economic protectionism, digital sovereignty, developing infrastructure, transitional regulation (take your pick, as appropriate). It means normal cellular roaming, as geared for visiting smartphone users, is typically capped at 90 days, sometimes less.

Which is unworkable for static monitoring units that are designed to stay in the field for a decade, at least. Certain countries have formalised such rules for IoT with restrictions on ‘permanent roaming’, whether as de jure bans (Brazil, Turkey, Nigeria) or de facto ones (China, Egypt, India, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, UAE). Elsewhere, mobile operators impose restrictions on permanent roaming with much the same result (as in Australia, Canada, US).

At the same time, there is a global regulatory clampdown on data sovereignty, limiting cross-border data flows. Which is about geopolitical control, of course – over data as a strategic asset, an economic driver, a security concern, and a citizen right (in whichever order you want). Regulation is real or pending: the EU’s GDPR privacy rules and Gaia-X sovereign cloud initiative; China’s cybersecurity and data security laws; India’s proposed personal data protection bill.

The net result for the niche IoT sector? The clunky old roaming model – using global SIMs in local deployments – is broken. Even the tangled eSIM proposition – which, on paper, is geared to solve local airtime headaches – is rendered impotent. The whole gamble about global IoT starts to look like a bust. That is, until this new SGP.32 variant arrives – some time in the second half of 2025.

Which explains why such hopes are pinned on it. Because SGP.32 is the solution – as a replacement, effectively, for the carrier-led SGP.02 standard for machine-to-machine (M2M) connectivity in eSIM devices, and as a complement, effectively, for the UI/UX-led SGP.22 mechanism for phones, watches, and other consumer gadgetry. In other words, it is designed for IoT. And yet, it is still a lot to get your head around – even if you’re in the IoT game.

And here’s why (also addressing the problem statement at the very end, there).

To be continued…